Overview

Introduction

- Review object-oriented concepts

- Introduce terms that describe the building blocks of an object-oriented language

- Review the role of compilers

- Present an overview of the course

"Surprisingly, C++11 feels like a new language: The pieces just fit together better than they used to and I find a higher-level style of programming more natural than before and as efficient as ever. If you timidly approach C++ as just a better C or as an object-oriented language, you are going to miss the point. The abstractions are simply more flexible and affordable than before." Stroustrup (2014)

Object-oriented programming is a computer programming paradigm for solving problems using objects and relationships between them. The objects are designed independently of one another and can be shared across a range of solutions that satisfy similar requirements. Object-oriented programming is well suited to application development, notably, large-scale application development.

This chapter reviews the object-oriented programming paradigm, introduces some of the building blocks common to many object-oriented languages, reviews the role of the compiler and summarizes the topics covered in this volume.

Object-Oriented Paradigm

The object-oriented paradigm frames programming solutions as sets of objects that interact with one another in their problem domain. Objects are instances of classes, where a class defines the structure of an object. Each object has its own state, which is stored in the form of the values of its instance variables or attributes. The functions that operate on an object's state are the member functions or methods of the class to which the object belongs.

Three Concepts

Object-oriented languages offer three high-level features for programming solutions:

- encapsulation

- inheritance

- polymorphism

Encapsulation

Encapsulation couples an object's data to the logic of its class. The class' member functions or methods define its logic. Typically, an object's data remains private to its class. Privacy helps preserve the object's integrity.

Encapsulation can be either weak or strong:

- weak encapsulation couples state and logic without implementing privacy;

- strong encapsulation couples state and logic and restricts access to an object's state.

Inheritance

Inheritance is the relationship between classes where one class inherits the entire structure of another class. The base class defines the structure to be inherited by derived classes or sub-classes. Each derived class defines the features to be added to the base class. The inherited features are the instance variables and logic of the base class. The additional features are the added instance variables and added logic.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism supports the multiplicity of behaviors for an identifier in an inheritance hierarchy. Multiple behaviors are associated with the same identifier. These behaviors are distinguished through an object's dynamic type. The language selects the behavior for the identifier that is appropriate to the dynamic type. The dynamic type of an object may change throughout the identifier's lifetime. As the type changes, the behavior associated with the identifier may change.

This flexibility is a distinguishing feature of object-oriented languages.

Modularity

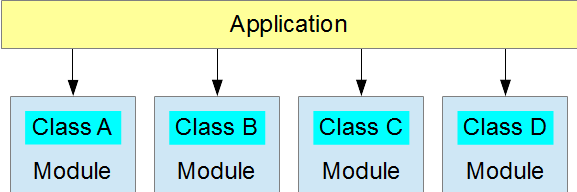

Object-oriented solutions lend themselves naturally to modular partitioning of source code. Modules define classes and their implementations. The source code for a module is stored in a file or file set. The file or file set holds a self-contained partition of that source code. Each module is compiled separately.

Updates to a specific module only require recompilation of that module along with those directly affected by the changes in the class definition. All other modules need not be recompiled.

Building Blocks

The common building blocks of an object-oriented language include:

- values

- objects

- variables

- references

- functions

- types

- class members

- templates

- namespaces

An object occupies a region of memory, holds a value and may have a name, but does not necessarily have a name.

A variable is a named object. It occupies a region of memory, holds a value and has a name.

The value that an object holds is the contents of the memory region allocated to the object and defines its current state.

Types

The type of an object relates the object to its underlying implementation and identifies the operations that the object can perform.

Type Categories

The types supported by an object-oriented language can be classified into categories based on their relationship to the underlying hardware facilities:

- fundamental types: correspond directly to the hardware facilities

- built-in types: reflect the capabilities of the hardware facilities directly and efficiently

- user-defined types

- concrete types: their representation is part of their definition and is known

- abstract types: their representation is not part of their definition and is unknown

Declarations

A declaration introduces a name into a program and associates that name with a type. The name is visible within the part of the program. That part of the program is called the name's scope.

Scope

The scope of a name extends from its declaration to the end of the code block within which the name has been declared. A block is a delimited set of program instructions. Methods of delimiting a block vary across languages.

The scope of a name may be any one of:

- local scope: the name has been declared within a function or code block

- class scope: the name has been declared as a member of a class

- namespace scope: the name has been declared as a member of a named block

- global scope: the name has not been declared in any one of the above scopes

Linkage

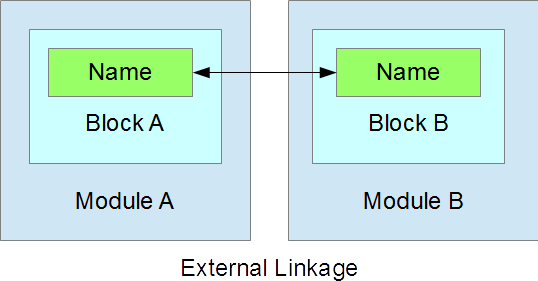

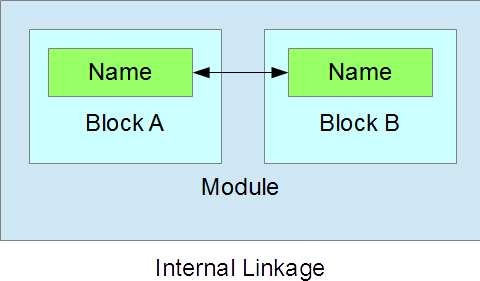

A name has a linkage if it can refer to an identical name declared in another scope. Linkage is optional. That is, the same name may refer to the same entity across different scopes. The name's linkage identifies its connectivity.

The linkage of a name may be

- external - connected across different scopes in different modules

- internal - connected across different scopes within the same module

- non-existent - not connected to any entity outside its own scope

Compilers

Compilers translate the source code of modules into binary code that is assembled to form a single executable version of program. The source code of a module is written in a specific language. Compilers are language specific programs.

Many languages are defined by an international standard. A language standard is an agreement amongst compiler writers, consultants, application programmers, and academics to implement a well-defined, minimal subset of the language used by the programming community at large. Coding to a language standard maximizes source code portability: a fully portable program compiles and runs without modification in a switch from one compiler to another.

Type System

Compilers use the type system of their programming language to translate source code into binary code. The type system provides consistency across the language's building blocks and identifies the operations that are admissible in forming expressions. The type system enables the compiler to check whether or not the relations between the building blocks are well-formed. The type system describes how to interpret the bit strings in memory. Source code that breaks the type system exposes the underlying bit strings in memory and thereby introduces uncertainty. In such cases how the compiler interprets the contents of memory is undefined.

The admissible operations on fundamental and built-in types are defined as part of the core of a language. The admissible operations on the user-defined types of an object-oriented language are specified by the programmer in the definition of those types. The compiler reports errors where the relations between these types are ill-formed.

Compiling, Linking and Executing

Source code may include some instructions that depend on information that is only available during the execution of the binary code. Programming such source code involves distinguishing times at which to check for compliance with the type system.

Verification of type compliance can occur at

- compile-time - during the compiler's translation of a module's source code into binary code

- link-time - during the linker's assembly of the binary code components for the modules that constitute an application, or

- run-time - during the user's execution of the binary executable.

Statically and Dynamically Allocated

In these notes, the terms statically and dynamically distinguish what can be determined at compile-time from what needs to be determined at run-time.

The term statically refers to anything that the compiler itself can determine for the module being translated without any link-time or run-time information. As programmers, we seek to translate and type-check as much of the source code as possible at compile-time. We refer to this as static type-checking and refer to a language that performs type-checking at compile-time as a statically typed language.

The term dynamically refers to anything that is determined during execution. As programmers, we refer to type-checking of dynamically allocated memory as dynamic type-checking and refer to a language that performs type-checking at run-time as a dynamically typed language.

Memory Distinctions

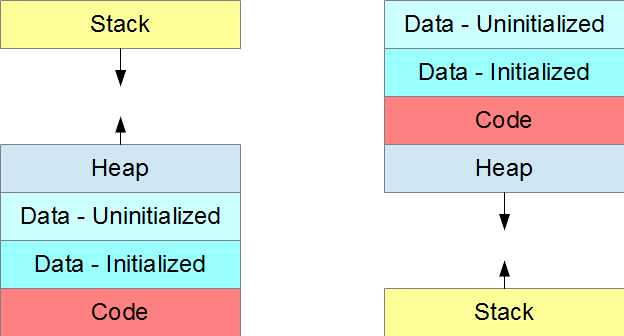

When an operating system loads an executable program into memory, it places the different parts of the program into different segments:

- code segment - stores the program instructions

- data segments - store data that survives the lifetime of the program

- stack segment - stores local data that is statically allocated

- heap segment - stores local data that is dynamically allocated

The size of statically allocated memory is known at compile-time. The compiler inserts the code to allocate this memory on the stack or data segment. Statically allocated memory is fast and deallocates automatically but cannot grow or shrink in size.

The size of dynamically allocated memory may be of variable size. This memory is allocated at run-time. The operating system provides this memory to the executable program in the size requested at that time. This memory is allocated on the heap, managed by the freestore manager and needs to be returned to the manager before it can be reused by the executable for some other purpose.

Most systems allocate heap and stack memory for an executable next to one another. In fact, on most systems, heap and stack memory expand in one another's direction as required.

Memory organization varies between operating systems and compilers. Possible organizations are shown below.

The Topic Groupings

The material covered in these notes is organized under six groups. Each group addresses a distinct aspect of object-oriented programming and is a collection of several chapters. These groups are entitled:

- Introduction - this overview, the building blocks of C++ and the compilation process

- Types - fundamental types, built-in types, class and enumeration types

- Class Relationships - inheritance, templates, compositions, aggregations and associations

- Processing - expressions, functions and error handling and reporting

- The C++ Standard Library - containers, iterators, algorithms, streams, pointers, and threads

- Deeper Detail - pre-processor directives, arrays and pointers, multiple inheritance, bit-wise expressions, linked list technologies