Error Handling

- Introduce exceptions and describe how to report them and how to handle them

- Describe different ways of terminating an application prematurely

"Prefer exceptions over error codes to report errors. Use status codes for errors when exceptions cannot be used" Sutter, Alexandruscu (2005)

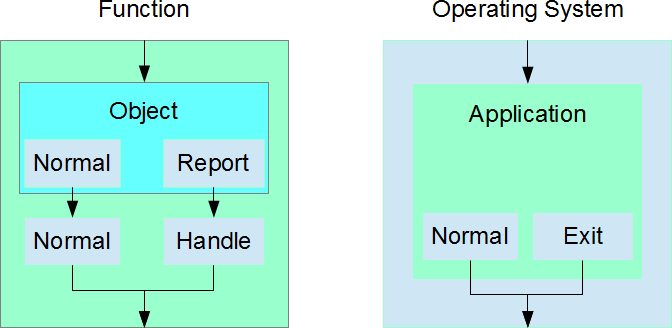

The modularity of object-oriented programs give rise to a separation of the cause of an error from the place where that error can be handled properly. Object-oriented languages require a specialized mechanism for identifying and handling errors. Since the designer of an object is not necessarily aware of how their object will be used, the object itself may not be able to handle the error(s) that it identifies. The preferred strategy in object-oriented programming is to identify the error as an exception to the normal execution process and to handle that error in some other as yet unknown object. The alternative strategy is to identify the error and call a specific library function, which will handle the error directly and immediately terminate the execution. These two strategies are illustrated below.

Structured programming requires passing an error code through return values or parameters up the function call stack to the function that handles the error, which presumes a known direct linkage between cause and effect. Object-oriented languages relax the single-entry single-exit principle of structured programming by uncoupling error reporting and handling. This automates the transfer of control from the reporting point to the handling point, invoking destructors where necessary.

This chapter describes the exception handling facilities supported by the C++ language along with the standard library functions that implement direct exit strategies.

Exceptions

An exception is something that is not done as one would normally expect it to be done. It may be a response to an initial attempt at a solution, a calculation that triggers a hardware error, or a warning about a questionable outcome. What is or is not an exception is within our discretion as programmers.

Reporting and Handling

Exception processing has two distinct parts:

- the exception is reported (or thrown)

- the exception is caught and handled

Reporting an Exception

The throw expression reports an exception and takes the form

throw expression;

expression is an expression of a previously defined type. A function that includes this statement cannot be identified as a noexcept function.

Handling the Exception

The code for handling an exception consists of two parts: the set of statements that initiated the process and the set of statements that respond to an exception. The keywords try and catch identify these complementary parts:

- a

tryblock contains all of the code that initiates whatever might throw the exception - one or more

catchblocks contain the code that handles any exception that was thrown as a result of executing any statement within thetryblock

The try ... catch combination takes the form:

try

{

// code that might generate exceptions

}

catch (Type_1 identifier)

{

// handler code for a specific type of exception

}

catch (Type_2 identifier)

{

// handler code for another specific type of exception

}

catch (...)

{

// handler code for all other types of exception

}

Type_1 and Type_2 refers to the type of the expression being handled. identifier is the name used within the catch block to refer to the expression that has been thrown. The first catch block that receives the type matching the reporting type handles the exception. The ellipsis (...) denotes any type not caught by the preceding catch blocks.

In the following example, the divide() function identifies two possible exceptions to a normal simple division of an element in an array. The two catch blocks in the main() function handle these exceptions:

- an array index that is out of bounds

- an attempt to divide by zero

// Exception Handling

// exceptions.cpp

#include <iostream>

void divide(double a[], int i, int n, double divisor)

{

if(i < 0 || i >= n)

throw "Outside bounds";

else if(divisor == 0)

throw divisor;

else

a[i] = i / divisor;

}

int main()

{

bool keepdividing = true;

double a[] = {1.1,2.2,3.3,4.4,5.5,6.6}, divisor;

int i, n = sizeof a / sizeof a[0];

do

{

try

{

std::cout << "Index: ";

std::cin >> i;

std::cout << "Divisor: ";

std::cin >> divisor;

divide(a, i, n, divisor);

std::cout << "a[i] = " << a[i] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Continuing ..." << std::endl;

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cout << msg << std::endl;

keepdividing = false;

}

catch(...)

{

std::cout << "Zero Division!" << std::endl;

std::cout << "a[i] = " << a[i] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Continuing ..." << std::endl;

}

}

while (keepdividing);

}

Index: 1

Divisor: -1

a[i] = -1

Continuing ...

Index: 4

Divisor: 2

a[i] = 2

Continuing ...

Index: 5

Divisor: 0

Zero Division!

a[i] = 6.6

Continuing ...

Index: 45

Divisor: 3

Outside bounds

The code within the try block is executed statement by statement as long as an exception is not thrown. Once divide() throws an exception, control leaves the try block. The throw statement transfers control to the first catch block that receives the type thrown.

If an exception is thrown and the run-time does not find any handler for that exception, the run-time calls std::terminate(), which terminates execution (see below).

Detecting an Exception

If an exception has been thrown, but has not yet entered a catch, the function int std::uncaught_exceptions() utility returns the number of uncaught exceptions in the current thread, during stack unwinding.

Standard Exceptions

The standard C++ libraries include a library of exception classes. The base class for the hierarchy of these classes is called exception and is defined in the <exception> header file. Classes derived from this base class include:

logic_error- handles problems in a program's internal logic, which in theory are preventable. The following classes are derived fromlogic_error:length_errordomain_errorout_of_rangeinvalid_argument

runtime_error- handles problems that can only be caught during execution. The following classes are derived fromruntime_error:range_erroroverflow_errorunderflow_error

bad_alloc- handles the allocation exception thrown bynew. This class needs the<new>header filebad_cast- handles the exception thrown bydynamic_cast. This class needs the<typeinfo>header file

In handling error objects from derived classes, it is important to catch the most derived types first. For example, the following code catches a std::bad_alloc exception before handling a general exception:

try

{

p = new char[std::strlen(s) + 1];

std::strcpy(p, s);

}

catch (std::bad_alloc)

{

std::cout << "Insufficient memory\n";

}

catch (std::exception& e)

{

std::cout << "Standard Exception\n";

}

The following handles all exceptions including the std:::bad_alloc exception under the first catch block

try

{

p = new char[std::strlen(s) + 1];

std::strcpy(p, s);

}

catch (std::exception& e) // called by std::bad_alloc also

{

std::cout << "Standard Exception\n";

}

catch (std::bad_alloc) // UNREACHABLE!

{

std::cout << "Insufficient memory\n";

}

Expressions that Throw Exceptions

Exceptions may be thrown by the following expressions:

- a

throwexpression - a

dynamic_castexpression - a

type_idexpression - a

newexpression

For the exception to be caught, it must be thrown from within a try ... catch block where the catch type match the exception type.

noexcept

C++11 introduced the noexcept keyword to identify a function as one that will not throw an exception. This keyword informs the compiler that it can perform certain optimizations that would not be possible if uncaught exceptions could pass through the function.

If a function marked noexcept allows an uncaught exception to escape at runtime, the program terminates immediately.

// No Exceptions - compile on GCC

// noexceptions.cpp

#include <iostream>

void d() { throw "d() throws\n"; }

void e()

{

try

{

d();

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cout << msg;

}

}

void f() { throw "f() throws\n"; }

void g() noexcept { e(); }

void h() noexcept { f(); }

int main()

{

std::cout << "Calling g:";

g();

std::cout << "Calling h:";

h();

std::cout << "Normal exit\n";

}

Calling g: d() throws

Calling h:

g() calls e(), which calls d(), which throws an exception. e() catches this exception and terminates normally. h() calls f(), which throws an exception. Since this exception is not caught before control reverts to h() and h() has been marked as a function that will not throw an exception; execution terminates abnormally at this point.

Standard Exits

The main() function of a program serves as its entry point and returns an integer to the operating system that conveys the program's status at exit time. This integer is the value of the expression in the return statement. C++ supports standard library functions that provide distinct routes to exiting a program other than through any normal return from the main() function.

The library functions that augment this normal termination mechanism include functions for:

- normal exits

- abnormal exits

Normal Exits

Normal exits involve calling the destructors that would be called at the end of each object's lifetime, flushing and closing all input and output streams and returning a status integer to the operating system. To simulate normal exits, C++ provides two functions:

int atexit(void (*)(void))int exit(int)

atexit()

The atexit() function registers a function to be called during any termination initiated by a call to the void exit(int) function. Each registered function must be of the form void (*identifier)(void)) where identifier is the name of the function. atexit() returns 0 if registration succeeds, non-zero otherwise. C++ supports registration of at least 32 functions.

exit()

The void exit(int) function initiates a termination process that:

- destroys objects with thread storage duration and associated with the current thread

- destroys objects with static storage duration

- calls functions that have been registered by

atexit() - flushes and closes all open C streams

- returns control to the operating system

For example,

// Normal Exits

// exit.cpp

#include <iostream>

void exit_1()

{

std::cerr << "In exit_1\n";

}

int main()

{

int i;

std::cout << "Return(!=1), Exit(1) ? ";

std::cin >> i;

if (i == 1)

{

std::atexit(exit_1);

std::exit(1);

}

return i;

}

will output the following (depending on the user input)

Return(!=1), Exit(1) ? 1

In exit_1

Return(!=1), Exit(1) ? 2

Abnormal Exits

Two functions initiate abnormal termination:

void std::terminate()void std::abort()

terminate()

The terminate() function terminates program execution as result of an error related to exception handling. Cases include:

- the mechanism cannot find a handler for a thrown exception

- the handler encounters the body of a function with a

noexceptspecification - the destruction of an object exits via an exception

throwwith no operand attempts to throw an exception when none exits

This function does not execute destructors for objects of automatic, thread, or static storage duration or call functions at addresses passed to atexit().

Since terminate() does not have access to the exception that was not handled, it is usually better to use catch (std::exception& e).

abort()

The abort() function terminates program execution by a SIGABRT signal. This function, like terminate(), does not execute destructors for objects of automatic, thread, or static storage duration or call functions at addresses passed to atexit().

Exercises

- Read Wikipedia on Exception handling