Smart Pointers

- Create program components using smart pointers

"Ensure resources are owned by objects. Use explicit RAII and smart pointers." Sutter, Alexandruscu (2005)

One of the principal uses of pointers in C++ applications is to identify resource variables. In a narrow sense, a resource is an object that a program does not possess at load time but acquires and releases during run-time. The most prominent example is memory on the heap (dynamically allocated memory). Other such resources include file handles, device interface objects and states of critical sections in multi-threaded applications. In a broader sense, a resource is any object created and released in a program, including not only an object on the heap as well as one on the stack or in global scope. In this sense, the owner of a resource is an object or piece of code that is responsible for the resource's release. Then, ownership falls into two distinct categories - automatic and explicit. An object is automatically owned if the mechanisms of the language guarantee its release. For example, a C++ object that is composed of other objects guarantees their release at the time of its own release (Milewski, 2001).

Pointers (as well as handles and abstract states) require explicit management of the resources to which they refer. For example, a pointer that holds the address of dynamically allocated memory retrieved using new requires the programmer to release that memory using delete. In other words, in C++, a raw pointer, like a file handle or the state of a critical section, has no owner that would guarantee its eventual release (Milewski, 2001).

A smart pointer offers a mechanism that makes the explicit management of a resource automatic. A smart pointer knows its resource. Unlike a raw pointer, a smart pointer, can manage the memory of the resource to which it points. It is a proxy for a raw pointer to the resource and looks like and feels like a raw pointer. It supports the dereferencing (*) and indirect member selection (->) operators. A smart pointer resides on the stack. When it goes out of scope, its destructor deallocates the dynamic memory to which it points or, in the case of a file handle, flushes the stream buffer and closes the stream.

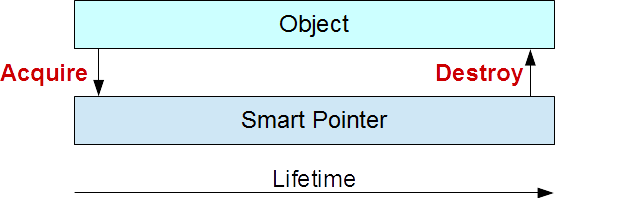

Smart pointers implement the Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) idiom of object-oriented languages. This idiom states that the acquisition of the resource occurs at initialization time; that is, at the same time as the memory for the pointer is created.

The need for smart pointers was in part motivated by the introduction of exception handling into the C++ language. The C++ standard library now provides several implementations of smart ownership. This chapter reviews the exception handling case and describes two categories of smart ownership: exclusive and shared.

Exception Handling

Throwing an exception can precipitate a memory leak.

A Raw Pointer Case Study

Consider the following class that includes a check on the validity of a person's title. The Title class holds the title (Mr., Ms., Dr.) in a C-style null-terminated string. The private validTitle() member function returns the address of a validated title. If the string is empty, this function throws an exception. The public display() query calls this private member function to report a validated title string:

// Smart Pointers

// Title.h

#include <iostream>

class Title

{

const char* title;

const char* validTitle() const

{

if (!title[0])

throw "invalid title";

return title;

}

public:

Title(const char* s) : title(s) {}

void display() const

{

std::cout << validTitle() << std::endl;

}

};

The throw expression needs to be caught.

The Memory Leak

Consider the following application that uses an object of the Title. The display() function allocates dynamic memory for a Title object, calls the display() function on that object, and deallocates the memory for the object t. Note that the private member function validTitle() called by member function display() may throw an exception and the global display() function does not catch any exception:

// Smart Pointers - Unsafe Exception

// unsafe_exception.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "Title.h"

void display(const char* s)

{

Title* t = new Title(s);

t->display(); // may throw an exception!

delete t;

}

int main()

{

const char* s[] = {"Mr.", "Ms.", "", "Dr."};

for (auto x : s)

{

try

{

display(x);

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cerr << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

Mr.

Ms.

invalid title

Dr.

Since the global function only deallocates the memory after the call to display(), a memory leak occurs whenever s is an empty string.

Fixing the Memory Leak

We could fix the memory leak by wrapping the call to Title::display() in a try-catch block:

// Smart Pointers - Safe Exception

// safe_exception.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "Title.h"

void display(const char* s)

{

Title* t = new Title(s);

try

{

t->display();

}

catch(...)

{

delete t;

throw; // continue throwing

}

delete t;

}

int main()

{

const char* s[] = {"Mr.", "Ms.", "", "Dr."};

for (auto x : s)

{

try

{

display(x);

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cerr << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

Mr.

Ms.

invalid title

Dr.

If the call to t->display() throws an exception, the global display() function will catch that exception, deallocate the memory and rethrow the exception.

This fix involves wrapping every call to Title::display() in every application in a try-catch block, which could prove to be quite cumbersome.

Taking Ownership of the Resource

The alternative solution to the possibility of a memory leak is simply to take ownership of the resource itself. Such a solution replaces the wrapping of every call to Title::display() in a try ... catch block with a linkage of the lifetime of the Title object to the pointer to it.

We link these lifetimes together through smart pointer classes. A smart pointer class acquires ownership of the resource at the same time that it allocates memory for the pointer to the resource (that is, at construction time) and deallocates the memory for the resource at the same time as it deallocates memory for the pointer to that resource (that is, at destruction time).

Consider the following templated class definition. This definition wraps the code for a raw pointer to a resource within a class that manages that resource:

// Smart Pointer

// SmartPtr.h

template <typename T>

class SmartPtr

{

T* p { nullptr };

public:

explicit SmartPtr(T* ptr) : p(ptr) { } ;

SmartPtr(const SmartPtr&) = delete;

SmartPtr& operator=(const SmartPtr&) = delete;

SmartPtr(SmartPtr&& s) noexcept

{

p = s.p;

s.p = nullptr;

}

SmartPtr& operator=(SmartPtr&& s) noexcept

{

if (this != &s)

{

delete p;

p = s.p;

s.p = nullptr;

}

return *this;

}

~SmartPtr()

{

delete p;

}

T& operator*()

{

return *p;

}

T* operator->()

{

return p;

}

};

Deletion of the copy constructor and copy assignment operator bars access to them. The move constructor and move assignment operator facilitate transfer of ownership of the object from one smart pointer to another smart pointer.

With this smart pointer to Title objects, there is no need for a try ... catch solution:

// Smart Pointer for title

// SmartPtr.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "Title.h"

#include "SmartPtr.h"

void display(const char* s)

{

SmartPtr<Title> t(new Title(s));

t->display();

}

int main()

{

const char* s[] = {"Mr.", "Ms.", "", "Dr."};

for (auto x : s)

{

try

{

display(x);

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cerr << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

Mr.

Ms.

invalid title

Dr.

The SmartPtr object resides on the stack, is automatically destroyed when it goes out of scope, and destroys its Title object at the same time. The indirect selection operator returns the Title pointer and through the indirect selection operator calls the display() query on the resource. Note that the delete t; statement is no longer present in the global display() function.

In summary, a smart pointer design supports:

- automatic initialization

- safe exception handling

- automatic destruction of the owned object at the appropriate time

Exclusive Ownership

The C++ Standard Library includes a smart pointer template for defining classes that manage one-to-one relationships between objects (or resources) and their pointers.

A unique smart pointer satisfies the following requirements:

- provides exception safety for dynamically allocated memory

- passes ownership of the object or resource on entering a function

- passes ownership of the object or resource on returning from a function

- collects the object or resource inside a container

As ownership passes from one smart pointer to another, the host pointer detaches itself from the object or resource and reattaches the object or resource to the new pointer. This move process does not duplicate or destroy the object or resource. A unique smart pointer

- owns its object or resource

- stores a raw pointer to its object or resource

- transfers ownership of the object or resource in move construction and move assignment

- calls its object's or resource's destructor when it itself is destroyed

- cannot copy construct or copy assign

std::unique_ptr

The library template named std::unique_ptr<> associates a smart pointer with a resource of specified type. This template is defined in the header file <memory>.

The following example uses this template to create a unique smart pointer for the Title object:

// Unique Ownership

// unique_ptr.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include "Title.h"

void display(const char* s)

{

std::unique_ptr<Title> t(new Title(s));

t->display();

}

int main()

{

const char* s[] = {"Mr.", "Ms.", "", "Dr."};

for (auto x : s)

{

try

{

display(x);

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cerr << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

Mr.

Ms.

invalid title

Dr.

Shared Ownership

Several smart pointers can share the same object or resource. Managing such many-to-one relationships for an object or resource requires reference-counting. A reference counter keeps track of the number of smart pointers currently pointing to the same object or resource. Only if this counter is 1, does a shared smart pointer destroy the object or resource when the pointer goes out of scope.

A reference-counted smart pointer

- stores a raw pointer to its object or resource

- shares ownership of its object or resource with other smart pointers

- transfers ownership of the resource in move construction and move assignment

- copies itself in a copy construction

- releases itself from its object or resource and reattaches itself in a copy assign

- can be compared for equality

- calls its object's or resource's destructor only if it itself is being destroyed and no other smart pointer shares ownership of the object or resource

std::shared_ptr

The standard library includes a template named std::shared_ptr<> that associates a resource-counted smart pointer with an object or resource. This template is defined in the header file <memory>.

The following example uses this template to create a resource-counted smart pointer for the Title object:

// Shared Ownership

// shared_ptr.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include "Title.h"

void display(const char* s)

{

std::shared_ptr<Title> t1(new Title(s));

t1->display();

std::shared_ptr<Title> t2(t1);

t2->display();

}

int main()

{

const char* s[] = {"Mr.", "Ms.", "", "Dr."};

for (auto x : s)

{

try

{

display(x);

}

catch(const char* msg)

{

std::cerr << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

Mr.

Mr.

Ms.

Ms.

no title

Dr.

Dr.

We prefer the more efficient unique smart pointer over a shared smart pointer where the unique smart pointer does the task. The unique smart pointer is ideal for passing ownership from one owner to another.

Exercises

- Read Code Project on C++ Smart Pointers

- Read informIT on Be Smart About C++ Pointers

- Read Bjarne Stroustrup on unique_ptr

- Read David Kieras on Using C++'s Smart Pointers

- Read Bartosz Milewski on Strong Pointers and Resource Management in C++