Multiple Inheritance

- Introduce multiple inheritance

- Describe how to resolve ambiguities among multiple base classes

"Except for friendship, inheritance is the strongest relationship that can be expressed in C++ and should only be used when it's necessary." Sutter (2005)

Some object-oriented languages restrict inheritance hierarchies to single lineages. C++ allows hierarchies of multiple lineage. A derived class may inherit the functionality of several base classes. An example is the fstream class of the C++ standard library, which combines the functionality of the ifstream class with that of the ofstream class. Candidates for multiple inheritance include omnivore (carnivore, herbivore), amphibious car (car, boat), clock radio (clock, radio), and cellphone (transmitter, receiver).

This chapter augments the material in the chapter entitled Inheritance and Inclusion Polymorphism by describing implementation of multiple lineages and resolution of ambiguity where multiple lineages derive from the same source.

Multiple Base Classes

The definition of a class that inherits from several base classes takes the form

class-key Class-name : Class-name-list

{

...

};

Class-name-list is a comma-separated list of the base class names. Each class-name may be prefixed by its own access modifier. Although there is no limit on the number of base classes in the list, no base class can be repeated. The access modifier for a base class applies only to that class and not to any subsequent class in the list. The default access modifier is private.

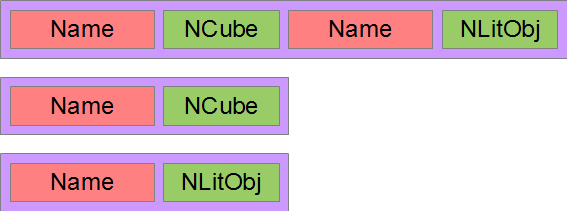

Consider a LitCube class that inherits the properties of a Cube type and a LitObj type. The LitObj class derives from an Emitter type. Emitter, like Shape, is an abstract base class:

The definitions for the Shape and Emitter abstract types are:

#ifndef SHAPE_H

#define SHAPE_H

// Multiple Inheritance - Shape

// Shape.h

class Shape

{

public:

virtual double volume() const = 0;

};

#endif

#ifndef EMITTER_H

#define EMITTER_H

// Multiple Inheritance - Emitter

// Emitter.h

typedef unsigned long int ulong;

class Emitter

{

public:

virtual ulong emission() const = 0;

};

#endif

A LitObj object holds a color in RGBA format, where the high order byte holds the red intensity, the next byte holds the green intensity, the next byte holds the blue intensity, and the low order byte holds the opacity. Each byte has a range of 0-255 for zero to full intensity respectively.

The definitions for the Cube and LitObj types are:

// Multiple Inheritance - Cube

// Cube.h

#include "Shape.h"

class Cube : public Shape

{

double len;

public:

Cube(double);

double volume() const;

};

// Multiple Inheritance - LitObj

// LitObj.h

#include "Emitter.h"

class LitObj : public Emitter

{

ulong color;

public:

LitObj(ulong c);

ulong emission() const;

};

The implementations of the Cube and LitObj member functions are:

// Multiple Inheritance - Cube

// Cube.cpp

#include "Cube.h"

Cube::Cube(double l) : len(l) {}

double Cube::volume() const

{

return len * len * len;

}

// Multiple Inheritance - LitObj

// LitObj.cpp

#include "LitObj.h"

LitObj::LitObj(ulong c) : color(c) {}

ulong LitObj::emission() const

{

return color;

}

The LitCube type combines the Cube type with the LitObj type.

// Multiple Inheritance - LitCube

// LitCube.h

#include "Cube.h"

#include "LitObj.h"

class LitCube : public Cube, public LitObj

{

public:

LitCube(double len, ulong c);

};

// Multiple Inheritance - LitCube

// LitCube.cpp

#include "LitCube.h"

LitCube::LitCube(double len, ulong c) : Cube(len), LitObj(c) {}

The two-argument constructor passes the initialization values to its two base class constructors. If we omitted these calls, the compiler would search for the no-argument constructors and report errors since none are defined. (Recall that a class definition that declares a constructor with arguments does not define a default no-argument constructor.)

The following example creates an instance of the LitCube type and displays its properties:

// Multiple Inheritance

// multiple.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "LitCube.h"

int main()

{

LitCube lc(2, 0xccdd33ffUL);

std::cout << "volume = " << lc.volume() << std::endl;

std::cout << "emission = " << std::hex << lc.emission() << std::dec << '\n';

}

volume = 8

emission = ccdd33ff

Replicated Base Classes

A class derived from two base classes that derive from the same base class replicates subobjects of that shared base class. The hierarchy shown below consists of an NCube class and an NLitObj class, each of which derives from a base class called Name. Each Name object contains a C-style string describing the object. (Note that we have removed the abstract base classes of the previous subsection.)

The class definition and implementation for the Name type are listed below:

#ifndef NAME_H

#define NAME_H

// Replicated Base Classes

// Name.h

class Name

{

const char* name;

protected:

Name(const char* n);

public:

virtual void display() const;

};

#endif

// Replicated Base Classes

// Name.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include "Name.h"

Name::Name(const char* n) : name(n) {}

void Name::display() const

{

std::cout << std::left << std::setw(MN) << name << std::right << '\n';

}

Granting the constructor protected access limits constructions of Name objects to the hierarchy.

The NCube and the NLitObj types derive from the Name base class:

// Replicated Base Classes

// NCube.h

#include "Name.h"

class NCube : public Name

{

double len;

public:

NCube(const char* n, double l);

double volume() const;

};

// Replicated Base Classes

// NLitObj.h

#include "Name.h"

typedef unsigned long int ulong;

class NLitObj : public Name

{

ulong color;

public:

NLitObj(const char* n, ulong c);

ulong emission() const;

};

The implementations of the NCube and the NLitObj classes pass the address of the C-style string identifier to the base class constructor and call the display() member function on the base class:

// Replicated Base Classes

// NCube.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "NCube.h"

NCube::NCube(const char* n, double l) : Name(n), len(l) { }

double NCube::volume() const

{

return len * len * len;

}

// Replicated Base Classes

// NLitObj.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "NLitObj.h"

NLitObj::NLitObj(const char* n, ulong c) : Name(n), color(c) { }

ulong NLitObj::emission() const

{

return color;

}

The constructor of the NLitCube class receives the identifier's address and passes the address to the base class constructors. The display() member function calls the member functions on both base classes.

// Replicated Base Classes

// NLitCube.h

#include "NCube.h"

#include "NLitObj.h"

class NLitCube : public NCube, public NLitObj

{

public:

NLitCube(const char* n, double l, ulong c);

};

// Replicated Base Classes

// NLitCube.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "NLitCube.h"

NLitCube::NLitCube(const char* n, double l, ulong c) : NCube(n, l), NLitObj(n, c)

{

}

The following example defines a LitCube object, a Cube object and a LitObj object. The display() member function is called on either the Cube object or the LitObj object:

// Replicated Base Classes

// replicate.cpp

#include "NLitCube.h"

int main()

{

NCube sc("a named cube", 2);

NLitObj sl("a named lit object", 0x55bb77aaUL);

NLitCube lc("a named lit cube", 2, 0xccFF33FFUL);

sc.display();

sl.display();

lc.NCube::display(); // through NCube

lc.NLitObj::display(); // through NLitObj

}

a named cube

a named lit object

a named lit cube

a named lit cube

The NCube and NLitObj objects each store the string identifier in their own subobject of Name type. The NLitCube object stores the string identifier in two separate subobjects of Name type.

If we were to call display() on a NLitCube object without specifying the intermediate class, the compiler would report an ambiguity in resolving the call. The cause of the replication/ambiguity is the duplicate attachment of the Name subobject to the NCube and NLitObj subobjects. Both the NCube and the NLitObj subobjects have their own Name subobjects. The compiler cannot distinguish which is preferred.

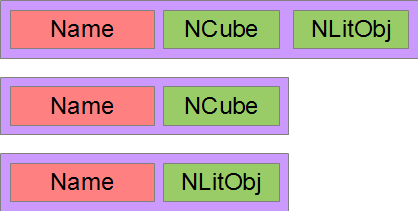

Virtual Inheritance

The solution to base class replication is virtual inheritance. We attach the shared base class to the most-derived class rather than to each derived class.

This allows the compiler to arrange the data in an NLitCube, an NCube and an NLitObj as shown below:

We upgrade our definitions of the NCube and NLitObj classes to derive from the Name type virtually:

// Virtual Inheritance

// NCube.h

#include "Name.h"

class NCube : virtual public Name

{

double len;

public:

NCube(const char* n, double l);

double volume() const;

};

// Virtual Inheritance

// NLitObj.h

#include "Name.h"

typedef unsigned long ulong;

class NLitObj : virtual public Name

{

ulong color;

public:

NLitObj(const char* n, ulong c);

ulong emission() const;

};

We update our implementation of the NLitCube constructor to call the Name constructor directly:

// Virtual Inheritance

// NLitCube.cpp

#include "NLitCube.h"

NLitCube::NLitCube(const char* n, double len, ulong c) :

Name(n), NCube(n, len), NLitObj(n, c)

{

}

The following example defines a LitCube object, a Cube object and a LitObj object. The display() member function is called on either the Cube object or the LitObj object:

// Virtual Inheritance

// virtual_inher.cpp

#include "NLitCube.h"

int main()

{

NCube sc("a named cube", 2);

NLitObj sl("a named lit object", 0x55bb77aaUL);

NLitCube lc("a named lit cube", 2, 0xccFF33FFUL);

sc.display();

sl.display();

lc.display();

}

a named cube

a named lit object

a named lit cube

With virtual inheritance, there is no ambiguity and we do not need to specify an intermediate class.

Exercises

- Read the Wikipedia article on Multiple Inheritance.

- Read the Wikipedia article on the Diamond Problem.